Gothic texts themselves can be hard to define as they are ‘seen as unstable, because its elements came to contaminate almost every other genre… [and] generated new genres’[1] but can be broadly described as encompassing darkness, supernatural and sinister ideas surrounding society.

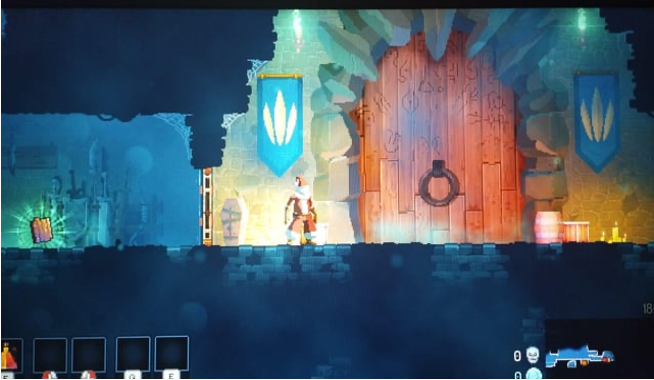

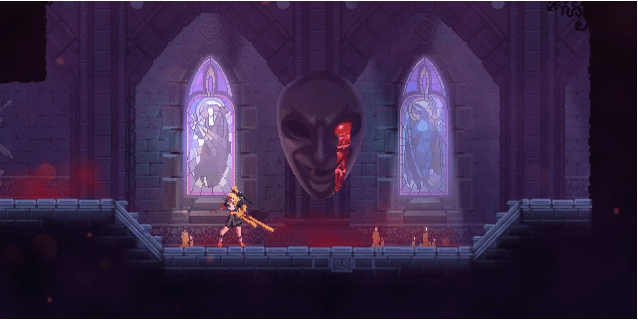

The overall graphics of this game can be seen as nothing short of gothic. Most levels feature rolling fog clouds, dark rooms, monstrous enemies, and broken buildings with dead characters left for the player to find. With burning sconces upon most walls, it is both stereotypically gothic at first glance, as well as also dealing with deeper gothic themes. Based inside a prison, the game tasks the player to find a way out to escape from the cruel world they have been ‘reborn in’. The story consists of an undead prisoner who must fight his way out of the depths to find what has happened to his homeland. With many references to the people in power sending a plague to the town, and hurting the residents, the player has a lot to learn. Just as Punter claims, ‘The Gothic is revealed a not an escape from the real, but a deconstruction and dismemberment of it.’[2] The themes of this game compliment that perfectly, as well as linking well to other Gothic texts.

A key theme of gothic texts is the idea of ‘The Uncanny’ which is a term mainly associated with Freud, meaning ‘at its core, an anxiety about the stability of those persons, places, and things in which we have placed our deepest trust, and our own sense of identity and belonging’[3]. Although it is associated with Freud, he was not the one to come up with this idea fully. He elaborated on it originally from German psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch in his 1919 paper ‘The Uncanny’[4].

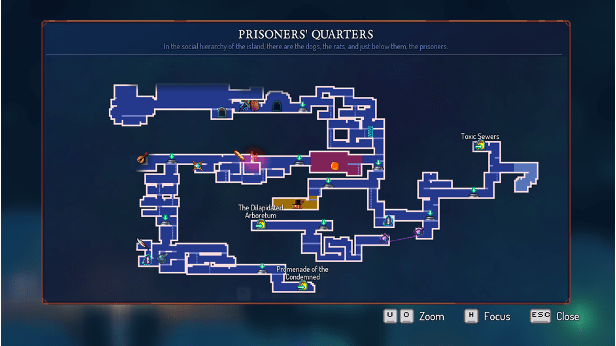

Dead Cells[5]is innately uncanny throughout many aspects of the game, from the genre to the storyline, there is a constant sense of unease for the player. Being a roguelike game, it is ‘structured around failing and restarting, in which no two play-throughs are exactly alike due to a design that randomises various aspects of the experience’[6]. This is important when linking to the theme of the gothic, as the player has a vague sense of understanding what is happening in the storyline, and whereabouts they are in the map- when even if they have played multiple times, the paths are different, and it very rarely the same. What makes it even worse, is that the very start of the game is always the same for the first 10 seconds. The player passes a large red door and collects the weapons before they begin the actual level itself. This can lead to a false sense of security, tricking the player into thinking they know what is coming up, but then turning it all upside-down. This sense of unease and finding familiar in the unfamiliar is exactly what Freud claims is the uncanny. It is not a just typical fear of seeing spooky or scary images or gameplay, but rather the unsettling feeling of not quite understanding what is going on even when at first glance looks normal and safe. It is looking at the weirdness of what should be the ordinary.

Furthermore, along with the paths changing each time the player dies, there are also multiple exits and endings for each level which adds another layer of confusion. Each exit leads the player to a different level which again changes with every death. What is key to note here is the use of liminal spaces throughout this game which ‘refers to transitional or threshold spaces where established distinctions and norms dissolve, creating a complex interplay of allure and terror’[7]. Between ‘real’ levels, there are areas that’s only use is to level up and gain experience. These levels exist almost outside of the main game. Whilst you must pass them to get further into the story, there is the option to simply rush through to reach the next level faster. In many of the biomes and stages, the player uses a lift system to stray away from the main path and enter smaller rooms where enemies and treasures reside. It takes a risk to touch uncharted territory, but it can be a worthy pay off.

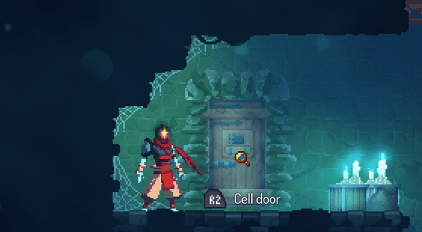

Building on this idea of liminality, the graphics of the game show many windows to the ‘outside’ that the player cannot reach. It leaves the feeling of entrapment and claustrophobia which are again key themes in the gothic. There are also many locked doors that the player passes which often cannot be opened, seemingly tricking the player into a sense that they can escape. Also, in certain areas, there are prison cells which allow the player to talk through them to an unseen character hidden behind. The text pokes fun at the player for being ‘on the wrong side of the door’, leaving an uneasy feeling.

Doors in general are a key part of this game, which link nicely to other Gothic texts. They allow both a rest bite from the constant onslaught of enemies, but also reveal deeper parts of the game. Keys must be found by killing enemies which give rewards like better weapons, but they can also open different areas of the map. However, whilst a select few of the doors can be opened, many remain permanently shut. The player can knock to interact with it, but nothing will happen which adds to the sense of disturbance the game causes. In The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde[8], doors are also a key feature. The first chapter is namely called ‘The story of the door’, and uses vivid descriptions of ‘The door, which was equipped with neither bell nor knocker, [being] blistered and distained’ (Jekyll and Hyde page 6). The strangeness of this is talked about throughout the novel, as well as there being links to other kinds of doors. The cabinet door in the laboratory suggests the two sides to a person, in this case, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and the good and evil that resides within. It also suggests secrecy and deceit which links right back to liminality.

Another way in which Dead Cells links to Jekyll and Hyde along with the gothic is through the idea of dualism. The player begins the game by picking up two weapons, and these weapons will stay with them throughout the game until new ones are bought or found. Typically, a long range and a short range are used, but this is not always the case. There is only the ability to have two weapons at all times, so it is up to the player to select the best. These can either be weapons that are used together in harmony, or ones with drastically different functions to potentially give better options in battles. Some weapons picked up automatically count as two, so this limits what can be achieved. The idea of always having two parts to the whole stems from duality- which is prevalent with the character of Dr. Jekyll whose personality splits into two separate personalities. Further to this, mirrors in gothic literature are integral as ‘The mirror is connected to the framework of the Gothic via the notion of the ‘double’, the terrifying Other that lingers in the margins of our consciousness and challenges our cultural certainties. In the reflection, the familiar becomes unfamiliar, the known becomes unknown, the certain merges with the uncertain.’[9] A mirror can be unlocked after a certain point of the game, which is uncanny as instead of reflecting the character as one would think, it shows future enemies that may be hiding more than they seem.

Finally, there are many more smaller links to the Gothic. There is a DLC which is based around fighting Dracula and travelling through his castle.

Some weapons also cause bleeding to enemies in which you can watch them bleed out. The blood links very well to the text Dracula[10] and to Interview with the Vampire[11] as that is a crucial part of vampiric understanding. The checkpoints also feature a swarm of bats which cross the screen bringing in yet more graphic interpretations of gothic imagery.

Overall, Dead Cells is unequivocally Gothic, and offers a more modern interpretation of what it means to be a gothic text.

Bibliography:

Anne Rice, Interview with the Vampire, 1997, New York Ballantine books

Bram Stoker, Dracula, Vintage Classic, 2019

Dead Cells, Motion Twin, Xbox

Greg Kasavin, Don’t Be Scared. Play a Roguelike, Haley Perry, Wirecutter, Published May 9th, 2023

Irina Rata, An Overview of Gothic Fiction, Volume 17, 2014

Lorna Piatti-Farnell, Gothic reflections: Mirrors, mysticism and cultural hauntings in contemporary horror film, Australian Journal of Popular Culture, volume 6, Issue 2, September 2017

Mariyam Farzand, Exploring Liminal Spaces in Gothic Literature: The Role of Transition and Boundary in Frankenstein, Dracula,and the Works of Edgar Allan Poe, October 2024

Marjorie Sando, Something’s Wrong in the Garden: the Uncanny and the Art of Writing, the Masters Review, October 5th 2015

Punter, David and Glennis, Byron. The Gothic. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2004

Robert Louis Stevenson, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Norton Critical edition

Sigmund Freud, The Uncanny, Penguin World Classics

[1] Irina Rata, An Overview of Gothic Fiction, Volume 17, 2014

[2] Punter, David and Glennis, Byron. The Gothic. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2004

[3] Marjorie Sando, Something’s Wrong in the Garden: the Uncanny and the Art of Writing, the Masters Review, October 5th 2015

[4] Sigmund Freud, The Uncanny, Penguin World Classics

[5] Dead Cells, Motion Twin, Xbox

[6] Greg Kasavin, Don’t Be Scared. Play a Roguelike, Haley Perry, Wirecutter, Published May 9th, 2023

[7] Mariyam Farzand, Exploring Liminal Spaces in Gothic Literature: The Role of Transition and Boundary in Frankenstein, Dracula,and the Works of Edgar Allan Poe, October 2024

[8] Robert Louis Stevenson, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Norton Critical edition- all further references given in body of the text

[9] Lorna Piatti-Farnell, Gothic reflections: Mirrors, mysticism and cultural hauntings in contemporary horror film, Australian Journal of Popular Culture, volume 6, Issue 2, September 2017

[10] Bram Stoker, Dracula, Vintage Classic, 2019

[11] Anne Rice, Interview with the Vampire, 1997, New York Ballantine books

Leave a comment